Scholarly Introduction: Rethinking Dickens's Serial Form with the DDNP

How to cite this page (MLA): Gibson, Anna, Adam Grener, and Frankie Goodenough. “Scholarly Introduction: Rethinking Dickens’s Serial Form with the DDNP.” Digital Dickens Notes Project. Anna Gibson and Adam Grener, dirs. 2022. Web. http://dickensnotes.com/introduction/general/

Serial Composition: Writing in Parts

The Digital Dickens Notes Project (DDNP) uses the Working Notes Charles Dickens kept for his novels after 1846 to offer a new approach to the study of these major Victorian texts and the serial form they epitomize. By immersing users in Dickens’s compositional practice over many months of serial writing, and in the iterative development of a serial novel’s form over time, the DDNP foregrounds process in reading and analyzing Dickens’s novels.

As readers and scholars, we typically approach Dickens’s compositional practice—and serial form more broadly—almost necessarily anchored in a position of retrospection: we look back from the vantage of the completed novel, with knowledge of the full arc of Dickens’s career, which is itself remediated through the substantial body of scholarship his works have generated.

But all of Dickens’s novels were—until the final installment was written and published—novels in process. They were open-ended and indeterminate, yet also delimited by the foundations laid in the preceding installments, as well as by the predetermined length of the individual installment and overall number of installments. Even amongst many contemporaries who published serially, Dickens’s novels were uniquely defined by the material circumstances of serial publication. For his novels published in monthly installments, each number was composed, revised, typeset, edited, printed, published, sold, then read (and even reviewed) by the public in discrete serial parts over the course of nineteen months.

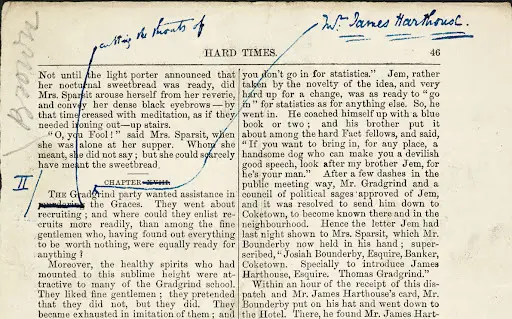

Serial form not only structured Dickens’s compositional habits as a novelist, but it also shaped the contours of his other professional commitments and the rhythms of his personal life. By the time Dickens came to write Hard Times for publication in Household Words in 1854, he found himself needing to conceive and compose the novel—as the Working Notes vividly illustrate—in the standard monthly installment size he had become accustomed to, before dividing those into smaller segments for weekly publication.

The Working Notes are evidence and a robust material record of Dickens’s navigation of serial production. The complete sets of Notes—both for individual novels and across multiple novels from Dombey and Son (1846-48) onwards—enable us to look back, retrospectively, and trace developments in Dickens’s craft. But the Notes, we believe, can also activate the contingency of serial composition and reanimate our engagement with the processual nature of Dickensian serial form.

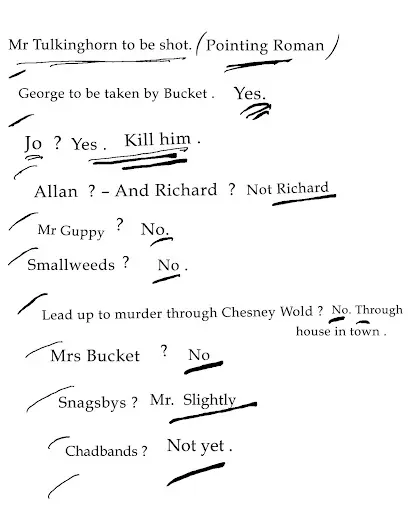

To take a basic but illustrative example: the left-hand memoranda of many Working Notes show Dickens posing questions to himself, frequently about the potential inclusion of specific characters in a given number, followed by answers that are (very frequently) in a clearly different ink or nib. These inscriptions on the Notes—query, followed by answer—are traces of the temporal distension of Dickens’s compositional process. Read alongside the often heavily edited manuscript pages of the novel, they cultivate a sense of potentiality and counterfactual possibilities within each number, as Dickens moves month by month from initial conception to completed novel. The Working Notes, in other words, offer us a point of engagement with Dickens’s serial novels that unsettles the finality of the published number or the completed novel.

Pattern and Process: Dickens as Story-Weaver

The tension between finished form and compositional process was central to Dickens’s own experience of his serial novels. In his prefaces, which he wrote immediately after finishing a novel, he often used the metaphor of weaving to name the conflicting pressures of the “general purpose and design” of the novel and “the temptation of the current monthly number” (Martin Chuzzlewit 5). In the preface to Little Dorrit (1855-57) (xxi), for instance, he made this plea to his readers:

[A]s it is not unreasonable to suppose that I may have held [the work’s] threads with a more continuous attention than anyone else can have given them during its desultory publication, it is not unreasonable to ask that the weaving may be looked at in its completed state, and with the pattern finished.

And in the “Postscript in lieu of a preface” to Our Mutual Friend (1864-65) (821), he repeated this weaving metaphor:

Its difficulty was much enhanced by the mode of publication; for, it would be very unreasonable to expect that many readers, pursuing the story in portions month by month through nineteen months, will, until they have it before them complete, perceive the relations of its finer threads to the whole pattern which is always before the eyes of the story-weaver at his loom.

In approaching Dickens’s texts via their temporally expansive composition, the DDNP takes seriously the tensions Dickens names between pattern and process, between prospection and retrospection, between complete form and serial formation, between weaving (noun) and weaving (verb).

The Working Notes, illuminated by the DDNP’s annotations, can indeed help us to perceive the “whole pattern” of a long, dense, overpopulated novel via as little as 19 pages of text, drawing attention to the carefully crafted, interwoven threads of plot. But they can also allow us to immerse ourselves in the “finer threads” that weave across, loop back, and interlace between the space and time of serial installments. We can notice as the weaver drops threads, changes his mind, and alters the pattern.

Exploring Seriality with the DDNP: Transcriptions and Annotations

To facilitate this engagement with Dickens’s serial practice, the DDNP offers users legible, spatially accurate transcriptions of the Working Notes with robust editorial annotations.

The DDNP’s transcriptions aim to translate the materiality of the Working Notes into digital images. Our transcription practices take into account not just the legible textual content of the Notes; we take just as seriously the spatial and visual properties of the page. In rendering non-textual markings (underlining, deletions, and check marks), and in preserving the layout of each manuscript page while making Dickens’s handwriting accessible, we aim to facilitate rich close reading of these compositional records. Immersing readers in Dickens’s multiple engagements with the page, our transcriptions turn these texts into dynamic spaces. Users can zoom in and out of transcriptions to examine the Notes in detail and compare the Notes’ content across novels. (For more on the creation of our transcriptions, see Editing the Notes).

The DDNP’s editorial annotations are the product of detailed archival research and provide an immersive engagement with Dickens’s compositional process and serial novel formation. Based on an examination of the Working Note manuscripts alongside many other archival traces of Dickens’s writing process—including his memoranda book, letters, the densely interlineated novel manuscripts, multiple sets of edited and corrected proofs, and the published installments of each novel—our annotations draw attention to the dynamics of serial composition.

In an attempt to access the “layers” of Dickens’s engagement with these Notes over time, we compare changes of ink in the Notes to the manuscripts and edited proofs; place changes and emendations in the Notes in the context of events in Dickens’s life made evident in his letters; and trace deletions, additions, and emendations across the multiple compositional documents (manuscript, multiple edited proofs) to understand the order and the manner with which Dickens used these pages. In many instances, analysis of the Working Notes enables us to establish plausible, though not necessarily conclusive, interpretations of the temporal relationship between the content on the Notes and the composition of the text. For example, evidence provided by the manuscripts and corrected proofs—such as changes to a character’s name within the manuscript pages, or the addition of a title in ink to the corrected proofs—confirms how Dickens used the Working Notes to record decisions or details after completing the composition of a given serial installment.

In addition to drawing attention to temporal layers and elements of compositional practice, our annotations also treat the Working Notes as interpretive tools for approaching Dickens’s novels. Notes can illuminate thematic elements of a novel, indicate the relationships between or handling of certain characters, and shed light on pacing and plot developments. Cumulatively, the annotations contribute to the DDNP’s efforts to cultivate an appreciation for the dynamism and open-endedness of Dickens’s compositional process, even as his career progressed.

Dynamic Records of Serial Process: Scholarly Approach

At the heart of this project is the conviction that the Working Notes are invaluable windows into the workings—the mechanisms, operations, and activities—of Dickens’s serial novel form. Our close inspection of the Working Notes alongside these supporting documents demonstrates that the Note system was critical to Dickens’s management of narrative over time, across a novel’s nineteen-month serial run. While the Notes often served planning purposes, helping Dickens think prospectively about what must be included in a given or future installment, they just as often served as retrospective records of what had already been accomplished. For instance, there are several instances where, after adding or emending a chapter title in proof, Dickens fails to make the change on the manuscript, but does return to add the new title to the Working Note. This suggests that he intended each Working Note to be an important distillation of a serial installment, and that he carried the Notes forward into subsequent months as important points of reference.

Our scholarly approach to Dickens’s Notes is thus a departure from traditional forms of scholarly engagement with the Notes, which have often been read as a residual trace of Dickens’s attention to design. The notes have been described as “number plans,” “blueprint[s],” “worksheet[s],” and “reminders”; as evidence of “authorial intention” and “systematic planning”; and as “ingredients for a particular number.”1 While Harry Stone (editor of the only complete scholarly edition of the Notes published in 1987) and others frequently acknowledge the complex temporality of the Notes,2 their position in Dickens scholarship to this point has been most often as illustration for Dickens’s increasing commitment to coherence and formal unity as his career progressed.3

But a closer engagement with the materiality of the Working Notes, and examination of these documents alongside the many records of Dickens’s serial composition, offers a much more dynamic picture of their complex temporality. Documents of process as well as pattern, they reveal both the constraints of the serial installment and the indeterminacies and openness of serial temporality. In Serial Forms Clare Pettitt reads seriality as an “exceptionally, perhaps even dangerously, flexible form” that can be both “emancipatory” and “regulatory”; it can produce restraint as well as freedom, systematization as well as dynamism (Pettitt 6-8). As a unique record of Dickens’s compositional process and practice, his Working Notes enable us to explore his navigation of serial form from Dombey and Son through the completed numbers of The Mystery of Edwin Drood (1870).

Given the inconsistency of Dickens’s practice with the Notes across a single novel, it is apparent that the Working Notes did not function as mere blueprints or even simple summaries. If Dickens, as the self-fashioned “story-weaver at his loom,” imagined his novels containing many threads that weave in and out, through and between, the Notes offer access to the texture of a work. They capture and visualize a dynamic back-and-forth movement between artistic compulsions—to plan, document, visualize, and reflect. The Notes are experimental spaces where Dickens laid down ideas for a number, fairly indiscriminately; later returned to make additions and changes; and finally recorded what had been “worked out” in the writing process. Consequently, the Notes seem to have provided him, month by month, with a sense of the shape of the novel-in-process, offering opportunities to reconsider what each new decision or development might mean for the installments yet-to-come. To this end, they act as crucial containers for the imaginative and creative labor Dickens performed in his manuscripts.

As we explain in our Editorial Methodology, our Project aims to immerse readers in the serial temporality and the material complexity of these compositional documents. Our User Guide explains how users can explore the Notes in dynamic, non-linear ways to trace, examine, consider, compare, analyze, and experience the Notes in relation to Dickens’s novels.

For additional insights into our project’s methodology, please see our article in the Victorians Institute Journal (2022).

Works Cited

- Bradbury, Nicola. “Appendix 3: Dickens’s Number-plans for Bleak House.” In Bleak House, edited by Nichola Bradbury, Penguin, 1996, pp. 992-1011.

- Butt, John and Kathleen Tillotson, Dickens at Work. Methuen, (1957) 1968.

- Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit, edited by Harvey Peter Sucksmith. Oxford UP, 1999.

- ——. Martin Chuzzlewit, edited by Patricia Ingham. Penguin, 2004.

- ——. Our Mutual Friend, edited by Michael Cotsell. Oxford UP, 1998.

- Gibson, Anna, et al. ”The Digital Dickens Notes Project.” Victorians Institute Journal, vol. 49, 2022, pp. 210-223.

- Herring, Paul D. “Dickens’ Monthly Number Plans for Little Dorrit.” Modern Philology, vol. 64, 1966, pp. 22-63.

- Laing, Tony. Dickens’s Working Notes for Dombey and Son. Open Book Publishers, 2017.

- Pettitt, Clare. Serial Forms: The Unfinished Project of Modernity, 1815-1848. Oxford UP, 2020.

- Poole, Adrian. “Appendix 2: The Number Plans.” In Our Mutual Friend, edited by Adrian Poole, Penguin, 1997, pp. 845-884.

- Stone, Harry. Dickens’ Working Notes for his Novels. University of Chicago Press, 1987.

- Sucksmith, Harvey Peter. “Introduction, Notes, and Appendix.” In Little Dorrit, edited by Harvey Peter Sucksmith, Oxford UP, 1999, pp. 692-714.

- ——. “Dickens at Work at Bleak House: A Critical Examination of his Memoranda and Number Plans.” Renaissance and Modern Studies, vol. 9, 1965, pp. 47-85.

- Tambling, Jeremy. “Appendix II: The Number-Plans for David Copperfield.” In David Copperfield, edited by Jeremy Tambling, Penguin, 2004, pp. 907-939.

Footnotes

-

“Number plans” (Butt and Tillotson); “blueprint[s]” (Sucksmith “Work” 47); “worksheet[s]” (Laing 11); “reminders” (Sucksmith “Introduction” 691); “authorial intention” (Tambling 907); “systematic planning” (Poole 845); “ingredients for a particular number” (Bradbury 992) ↩

-

Harry Stone reads the notes for their insight into “Dickens in the act of creation” (xxvi). ↩

-

For instance, John Butt and Kathleen Tillotson, in their study of Dickens’s compositional practice, consider the Notes as the cornerstone for Dickens’s intricate craft, and Paul Herring acknowledges the Notes’ central function in facilitating the complex networks of interrelation in Little Dorrit. ↩